The Heavy Rider’s Disadvantage

“It could be debated if you can call it unfair, but heavy riders do suffer a disadvantage in Zwift races. The lighter riders have an easier time uphill and it is so hard to match the Watts needed to keep level with the lighter rider’s W/kg there.“

The above is a very common complaint on various Zwift forums. But is it true?

I like to question those self-evident truths we all take for granted. If they are indeed truths then there is no harm in validating them. Sometimes, however, they turn out not to be true after all, once you actually take a serious look at them. So what about rider weight and race results in Zwift? Let’s take one of those serious looks for a change instead of just passing on what some other guy said in a one-liner on the forum.

The Light Rider’s Advantage

Without any prior knowledge about the impact of weight in Zwift racing we could assume three things:

1. There could be advantages to being light

2. There could also be disadvantages to being light

3. If there are both advantages and disadvantages to being light, perhaps depending on scenarios, then you could compare those advantages and disadvantages, weigh them against each other, and come to some kind of conclusion regarding the net effect of being light – is it more good than bad to be light, or is it the other way around?

So let’s start by looking at possible advantages to being light, since people say there are such advantages. There are no obvious advantages on the flat, and everyone seems to agree (we will get into details on this further down). What heavier riders say instead is that they have a hard time against light riders in climbs.

On the flat speed is mainly maintained by momentum, so pure Watts is king and heavier riders can usually (although not necessarily) push higher Watts than a lighter rider with a smaller frame and less muscle volume. But in a climb W/kg is king. Body weight comes into play, and maybe it is easier for a light rider to attain a better ratio between Watts and body weight than it is for a heavier rider, especially a heavier rider with a few surplus kilos.

The above is reasoning taken from riding outdoors and in a different setting than Zwift racing with its unique and uniquely stupid rules. But it is actually a completely flawed argument and you need to fully understand why. The explanation is two-pronged. We start off with some physics.

Question: A rider at 90 kg is time trialing against a rider at 70 kg up the Alpe du Zwift climb. Both are keeping the exact same lines and both are able to keep dead steady, ERG-like Watts. Both are doing exactly 3.19 W/kg. Who will win?

Answer: The lighter rider will win. By a few seconds. But it has nothing to do with Watts or weight. The lighter rider will win because he has an ever so slight advantage in drag, having a smaller frontal area.

It’s similar to choosing between bikes in your garage before a Zwift climb. One frame will be ever so slightly faster than the other. However, when was the last time you saw a race up AdZ and only that? There are no such races. The closest you can get to that scenario in a Zwift race is a race on Road to Sky, a route which has quite the approach to the mountain, and the approach is flattish. So if we staged an iTT on the Road to Sky course, then this advantage in drag for the light rider, a mere seconds, is more than offset by the heavier rider’s advantage on the flattish approach to the mountain. On Road to Sky, or even Ven-Top with its very short approach, the heavier rider will win!

Also, what you need to understand is that if it wasn’t for the small difference in drag between the two riders, if they both raced in vacuum, then if both started at the same time at the foot of the climb, both riders would arrive at the finish exactly simultaneously. Because if we ignore the drag issue, then 3.19 W/kg is 3.19 W/kg. It doesn’t matter what you weigh. You will travel up the mountain at exactly the same speed. That’s what the measure W/kg implies, it’s its purpose, to equalize riders to make a comparison possible.

A heavier rider could in theory have a hard time producing high enough Watts to be able to match the W/kg of a lighter rider in a climb. But in our example we assumed that both climbed at exactly 3.19 W/kg, so the heavier rider already compensated his higher weight with higher Watts. And thus they are both traveling at the exact same speed up the mountain.

Now here comes the second prong of the argument. Put the above in relation to the W/kg cat system, with the performance ceilings in cat B-D. To be competitive in any cat B-D, you typically need to be able to put out W/kg at or very close to the performance ceiling, be it 2.5 W/kg, 3.2 W/kg or 4.0 W/kg. So to win a race on any course in, say, cat C, you need to be able to hold 3.19 W/kg, or someone else could come and do the 3.19 W/kg and beat you (there’s plenty of such riders). Agreed?

So to win a race up AdZ you thus need to be able to hold 3.19 W/kg. Assume you are contender, someone who could actually win in cat C. Then you will be able to race Road to Sky at 3.19 W/kg. If you are indeed one of those riders who could, then as we just concluded your weight doesn’t matter at all. And we already know that there are heavy riders who can do 3.19 W/kg up AdZ, and there are light riders who can do the same. Both kinds race up the climb at almost the exact same speed, bar the minuscule difference in drag. In fact, given that you are a contender, you advantaged being heavy on Road to Sky since you will be naturally faster in the approach and might thus either get a head start or save some energy before the climb.

GET THIS:

There is no advantage to being light in Zwift racing!

And this is because of the W/kg cat system. Without it things would be different. With a results-based categorization, a race on Road to Sky would favor lighter riders, whereas the heavies would still reign on Tempus Fugit. You would have to specialize and play to your unique advantages, just like in real cycling.

So if there are no advantages to being light in Zwift, could there still be disadvantages?

The light rider’s disadvantages

This post is named the Light Rider’s Curse, which refers to a tendency in Zwift racing. Many light riders have first-hand experience of improving fitness to the point where they reach the top of their current race category. Or rather what should have been the top of the race category. Only it isn’t.

You would think that being able to average e.g. 2.5 W/kg in cat D would make you competitive there. But that is not necessarily the case. First, you have to beat the cruisers. But even if we take the cruisers out of the picture, it can still be surprisingly hard for a light rider to get anywhere near a podium in the average Zwift race.

So they do what anyone would do in that situation. They try to improve fitness further still. Shouldn’t that help getting to a podium then? No, that’s just that final push that tips them over to the bottom of cat C. They got upgraded before they even saw a podium.

Why is this? Is this real or just some bad excuse from failed light racers? It all seems so counter-intuitive. As a light rider you should have an advantage against the heavies in the hills, said a guy in a one-liner on the forum. And being able to do 2.5 W/kg you should have no problem getting a decent shot at the podium, right? So why don’t you win?

It’s because of this:

Someone doing 300W on the flat is going faster than someone doing 275W.

Yeah, of course he is! So what?

Well, what if it’s a semi-flat cat C race and the guy doing 300W weighs 94 kg? That’s 3.19 W/kg, within ZP’s cat limits. And what if the guy doing 275W weighs 77 kg? That’s 3.57 W/kg, way over limit. See the problem?

The heavy guy wins the race and the light guy, being slower, isn’t anywhere near a podium but is still a disgusting sandbagger who deserves a DQ. But this never happens in real-world cycling, only in Zwift. And it’s because of the W/kg cat system that no other sport uses.

Specifically, it’s because of the W/kg ceiling of the lower cats in combination with ZP disqualifying racers afterwards, racers that they themselves allowed into the race. But you can’t have a performance ceiling in sports. And you should never have to disqualify a contestant for being “too good” in sports.

Most races consist of mainly flattish stretches and then some shorter climbs. At the W/kg ceiling of a cat, i.e. in that front group with the riders that actually have a chance to win the race, a light rider can in theory never match the speed of a heavier rider without going over limits and getting a DQ or even an upgrade, not unless the heavier rider is a cruiser. It’s simple maths.

If it’s simple maths in theory, then it should show in data too. So does it? Let’s find out!

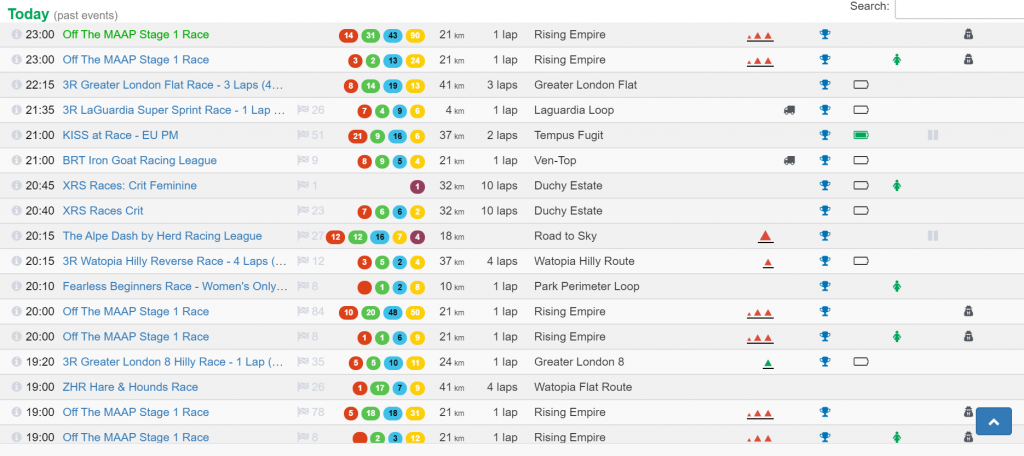

Weight Study 1 – A Mix of Races

I grabbed some fresh data from ZwiftPower, a sample of 50 consecutive cat C races of all sorts (distances, elevation, etc). I only skipped races where

i) weight data was missing

ii) there were fewer than 6 cat C finishers according to ZP

iii) the race type didn’t lend itself to this test (like e.g. Hare & Hounds, age category or TTT races).

Then I compared the average weight of the 3 riders on the podium to the average weight of the other riders in the race (hence why I wanted at least 6 finishers).

Results

The podiums in the races had an average weight of 81.3 kg.

The remaining riders in the races had an average weight of 77.5 kg.

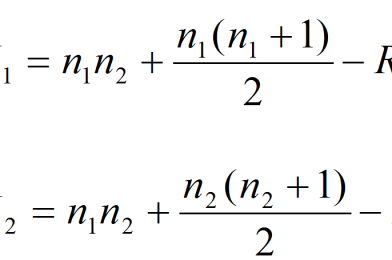

This nearly 4 kg difference between the average podium winner and the average loser turns out to be highly statistically significant, even at the 1% level (p = 0.00118). For those who aren’t into statistics, this means that it is extremely unlikely that this difference wouldn’t appear again and again if we picked some other random set of 50 races from the ZP database. And thus we can’t refute that there is indeed a difference in average weight between winners and losers. Winners are somewhat heavier on average. It is not bad to be heavy in Zwift racers, quite the opposite. It is bad to be light in Zwift races. The results prove it.

The W/kg cat system screws light riders. I will give a more detailed example than the the simple theoretical one above. Let’s work through this.

Assume the following:

-You are racing in the front group in cat C (for some reason there are no sandbaggers this time…)

-The group keeps a steady pace and you are at least 20 min from finish

-You weigh 75 kg

-You are on the wheel of a bigger guy @ 85 kg

-You are both in draft

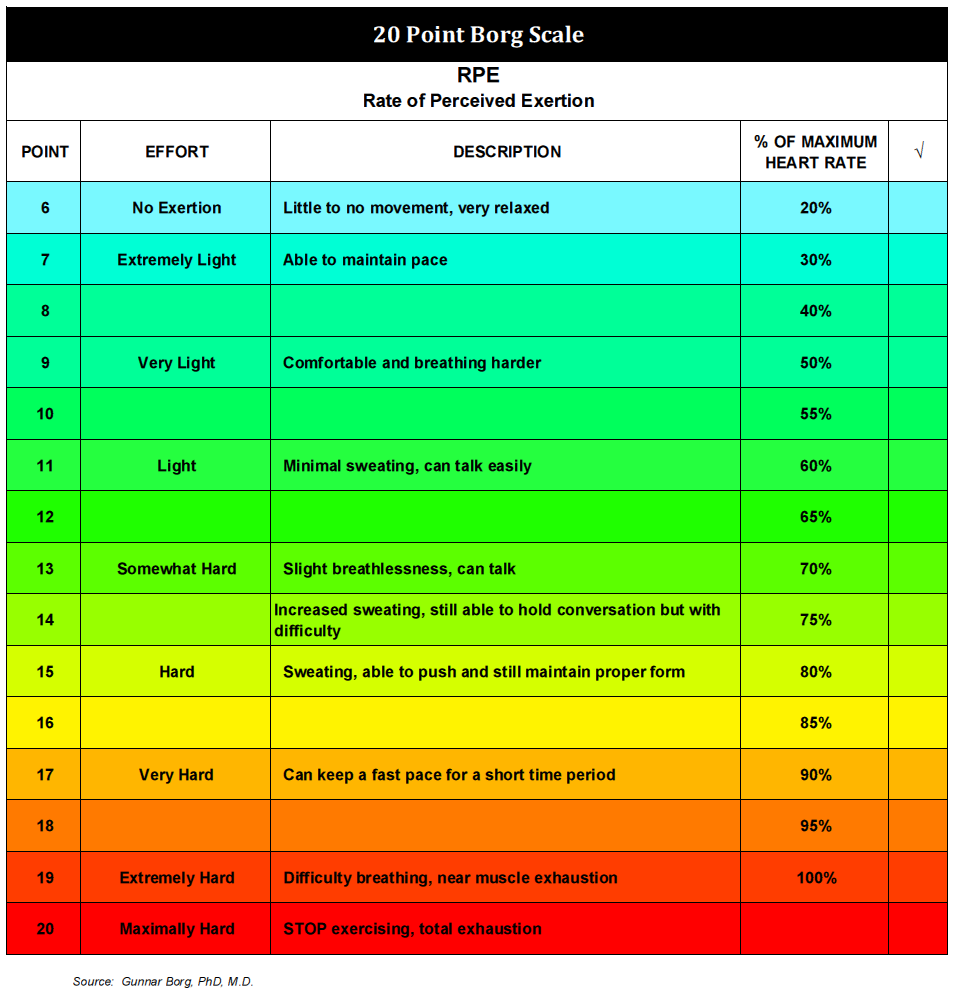

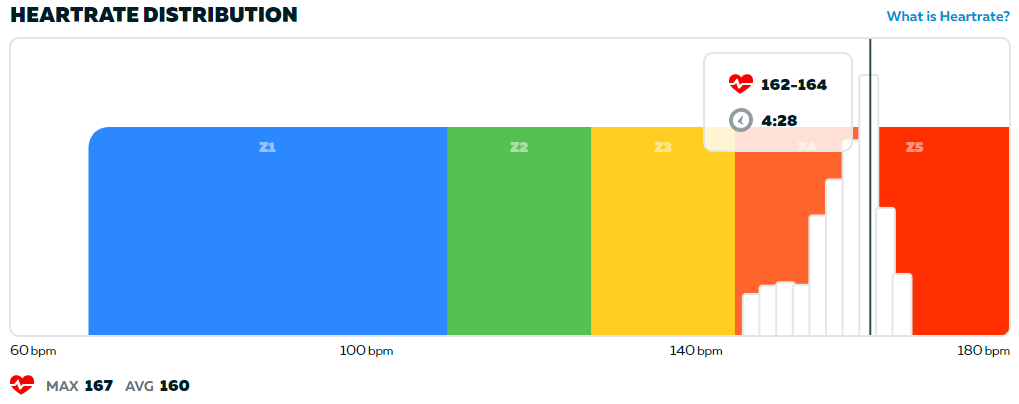

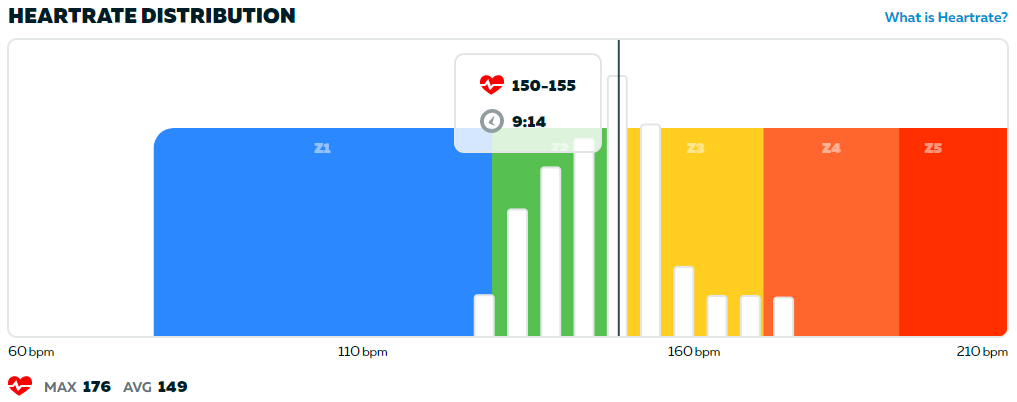

-The big guy is able to hold a 20 min average of 286W, i.e. 3.2 W/kg according to ZP (286 x 0.95 = 272. 272/85 = 3.2)

The only way you can stay on his wheel is by matching his 286W. This would put you at (286 x 0.95)/75 = 3.6 W/kg. Keep at it for 20 min (if you can) and ZP will give you a DQ. People might even call you a sandbagger! You simply can’t win this race as a light rider and get away with it on ZP. It’s not just hard. It’s impossible.

Guys weighing 75 kg with a 1 hr FTP of 272W according to ZP will already have been upgraded to cat B. They will have seen very few podiums back in cat C if they were up against heavier riders. Which they were. And data supports our simple maths theory and the existence of a Light Rider’s Curse.

The Objection

But wait a minute! “Assume you are both in draft…” Granted, draft in Zwift doesn’t give quite as much help as outdoors but it is certainly a factor. What if these heavier winners are just better at drafting? It seems unlikely. Why wouldn’t drafting skills be evenly spread out over riders of all weights and sizes? But it’s a good idea to eliminate draft when you are doing a study like this. So how could we eliminate it? By studying only individual time trials instead. On a TT bike you can’t draft.

Weight Study 2 – Only TT Races, No Draft

So instead I scraped 40 consecutive iTT races in cat C from ZP. What were the average weights for the podium vs the rest of the field? Was there a difference? And was it statistically significant (i.e. not random)?

Results for iTT’s in Cat C

Podium avg weight: 83.9 kg

Losers avg weight: 78.1 kg

Difference: 5.8 kg

Statistical significance: p=0.00004 (probability of a random sample/event resulting in such a difference)

Conclusion: The difference is not random. In fact, a pharma company doing a study on a new promising medication would do wheelies and open up the champagne if getting results of this magnitude. So heavier riders do have an advantage in cat C, even in iTT’s where there is no draft.

“Ok, but maybe this is exclusive to cat C. I don’t care about the fat noobs in cat C anyway. I race in B.”

So let’s look at cat B too.

Results for iTT’s in Cat B

Podium avg weight: 77.7 kg

Losers avg weight: 73.0 kg

Difference: 4.7 kg

Statistical significance: p=0.00007

Conclusion: The difference is not random. We can see that people weigh less in cat B, just as I predicted in and older blog post, but there is still a clear advantage for the relatively heavier rider, even without draft.

“Uh-oh… and you mean the reason for this is that both cat C and cat B have a performance ceiling (3.2 W/kg and 4.0 W/kg) that will weed out lighter riders trying to match the speed of heavier riders?”

Exactly!

“A-ha! Gotcha! But cat A doesn’t have a performance ceiling! So if their iTT winners are heavier than the losers too, then your argument implodes!”

Yes, that’s right. It would. We’d have to come up with some other explanation for the differences. Not that I can think of any. But let’s worry about that later. First let’s look at cat A the same way. If we see the same difference, then I’m in trouble. However, if we don’t see the same difference… then the W/kg cat system is in trouble. If I lose, I’ll go jump off a bridge. If the W/kg cat system loses then… it can go jump off a bridge.

Results for iTT’s in Cat A

Podium avg weight: 68.8 kg

Losers avg weight: 69.9 kg

Difference: -1.1 kg

Statistical significance: p=0.18

Conclusion: There is a small difference, but it is pointing in the other direction (better to be light) and it is quite possibly just random. We would get a difference like this almost every 1 in 5 samples from the ZP database. So we conclude that there is no difference in weights between podiums and losers in cat A iTT’s. There is no disadvantage to being light in cat A, where there is no W/kg ceiling stopping you from doing your best.

GET THIS:

There is no advantage to being light in regular Zwift racing, but there are clear disadvantages. Hence the net effect of being light is negative. Or to spell it out: It sucks to be light in Zwift. Heavies have the upper hand. Always, on any course.

The Light Rider’s Curse is a reality. Now where’s that bridge? I have a cat system to escort there.

And don’t you ever come to the forums and complain about being heavy again. You are wrong. Don’t spread misinformation. Either you are not able to perform at the performance ceiling in your category, and then it doesn’t matter if you are light or heavy. You will get dropped in a climb either way. Or you are a real contender and can touch the upper W/kg limit, and then you are not disadvantaged at all by being heavy. In fact, you have the upper hand.

The Takeaway

So what is your takeaway from this post? That you should go buy some cake, french fries and some jars of peanut butter and start gaining weight? No, it’s not weight per se that gives an advantage but the part of it that is muscle volume. And we are talking muscle volume in absolute terms, not relative terms where you factor in body fat.

If you are a little chubby with a nice dad bod but stay on top of your category in terms of W/kg, then you still more than likely have higher absolute muscle volume than a rider 30 kg lighter than you. This translates into higher Watts. And that still gives you an advantage, even if that lighter rider can produce the same W/kg as you.

Of course you only stand to gain from losing excess body fat. It will improve your W/kg if nothing else. Just watch it so you don’t get that dreaded upgrade. You can always do what I do. Cruise!