Have you ever participated in a Zwift race and had that sinking feeling that someone, or maybe several other riders, were actually cheating. Chances are you were right. Because cheaters like me exist for real. We come in many forms and sizes. I will go through the most common forms of cheating below, so you know what you should look out for in case you didn’t already.

Hackers

A hacker will manipulate either hardware or software, or both, to gain an unfair advantage. On rare occasions when freeriding you can see somebody zoom past you at superhuman speed and W/kg. Such blatant hacking is very rare in races. If it happens, or rather, to the extent it happens, it is going to be far more subtle. Why expose yourself that much as when going 20 W/kg as it is only going to get you DQ’d, if not for hacking then for going over the set W/kg limits in any race category (no, you couldn’t get away with it even in A+).

I am not going to point you in any direction, but if you google around a little, you will find examples of tech savvy guys who have invented ways to manipulate the power reporting in smart trainer hardware or in software, just to prove that they could. What you will not find are the ones who didn’t tell you about it and who might actually be using it in real Zwift races against you.

Fortunately, I am convinced this form of cheating is very rare and nothing you will generally have to worry too much about. Cheating this way requires special know-how that few possess. It could also be too hard for you to spot anyway. Likely, Zwift itself is probably in the best position to detect deviances in power input or similar that should raise suspicions.

There are cases – you can google for those too – where suspected hackers have been DQ’d for performing ‘too well’. There is, for example, the case with a Swedish MTB rider, mostly unknown on the international scene, who got DQ’d in a big Zwift event for this reason. He disputed the DQ and Zwift sent him a Tacx Neo for referencing his W/kg. He could reproduce his Watts even on the new rig but from what I heard Zwift wouldn’t lift the DQ. Was he cheating? Probably not, or I don’t know. What we learn from it, though, is that Zwift takes hacking seriously. In that regard they are probably not much different from any other online game provider, which will typically ban subscribers on indications of hacking.

But the case with the Swedish MTB rider also leads us into another form of cheating. Sometimes you don’t have to actively manipulate hardware to gain an unfair advantage. It can be enough to – purposely or not – neglect to maintain your hardware properly. A miscalibrated smart trainer can produce excessive Watt reporting. Can it be systematically exploited in races? Of course!

Know this: I will never hack in order to cheat in Zwift.

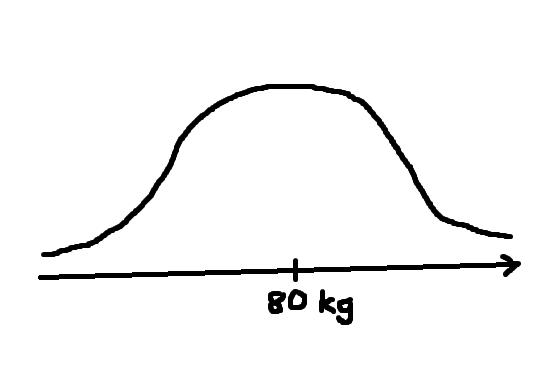

Weight Watchers

Want to do better in Zwift? Improve your W/kg! This can be done in either of two ways, looking at W/kg as a mathematical expression. Either you start producing higher Watts, i.e. you have to become stronger or more aerobically fit, or you lose weight. Oh, and there is a third option as well. You can just enter a false weight in your Zwift profile. People who underreport their weight in Zwift gain an unfair advantage. This is cheating. Sometimes people will even overreport their weight in order to cheat, but that is a special case we will discuss later and under a different heading.

How can you tell that somebody is cheating with his weight? You can’t. Normally, you can’t. Sometimes, when looking at people’s ZwiftPower profiles, you notice they have suddenly dropped significantly in weight from one day to the next. It could be a case of “I didn’t want to get on the scales until I knew for sure I had lost weight as to keep motivation and not disappoint myself, sorry!” That would be unintentional cheating. But most of the time it is somebody who got tired of getting ‘bad results’ and decided to take a little shortcut, i.e. a regular cheater.

Know this: I don’t weigh in before a race. I base my weight on the last morning weight. I check my weight fairly frequently although sometimes I might be sloppy and won’t check for some time, but I will never cheat with weight on purpose.

Shorties

A perhaps lesser known fact is that not only weight but also your height affects your speed in Zwift (and IRL). It does so because it affects air resistance. There is no wind in Zwift but the air resistance is very real and noticeable and is modeled on real life, or real physics.

Air resistance is an exponential counter-force to your pedaling. The faster you try to go on a bike, the more you will notice that counter-force. At speeds up to 25-26 km/h it isn’t so bad, but above that it gets worse and worse for every little speed increase. Accelerating from 20 km/h to 30 km/h isn’t hard. It is far harder to go from 30 to 40 on the flat, even though the relative speed increase is the same!

That is the effect of air resistance and it is a function of air density, which depends on altitude, and on the expression CdA, or Cd x A. Cd, or drag coefficient, depends on your geometrical aerodynamic shape. Low is better here. A cardboard box has a higher Cd than a ball. Note that it says nothing of the size of the object, just the shape, so a big ball has the same Cd as a small one. IRL you can affect your Cd by getting an aero bike, getting into the drops, tucking etc. Or by losing weight and getting thinner. Then we have the A component, and that is your frontal area. Now, Zwift reckons that if you are tall, then you have a bigger frontal area. It seems to be true that weight does affect your frontal area in Zwift, like it should.

At any rate, as with W/kg, if you want to go faster by reducing your CdA, there are two ways about it. Either you decrease your Cd, and you can’t, not in Zwift, except when changing bikes or going into the so-called ‘supertuck’ in descents at speeds at or above 57 km/h. Or you decrease your frontal area, A. This you can do easily. You just enter a lower number in the height field in your Zwift profile.

Most people who start a Zwift subscription, even most people who sign up on the 3rd party ZwiftPower website to get their race results validated, don’t know about the importance of height when they sign up. So it is often quite obvious when people cheat with height. Suddenly, from one day to the next in their ZwiftPower profile, they drop 10 cm in height. That’s a cheater. You gain and lose weight but you don’t swing up and down like that in height. Any changes to somebody’s height is highly suspicious.

Know this: I will never cheat with height. I am 185 cm tall and fairly skinny. Or have been for all of my adult life. Eventually I might shrink a little from old age but I doubt I will be zwifting then.

Sandbaggers

A sandbagger is a broad, fuzzy and frankly quite bad term for any zwifter who signs up to a race category below his abilities in order to get an unfair advantage. You thought he was your peer and that you would race fair against him, but then it turns out that he has superpowers and hits you by surprise from behind, often already at the start. Formally, this is not cheating since Zwift will allow an A+ rider to join a D race.

In order to prevent sandbaggers ZwiftPower (ZP) arrived at the scene as some kind of UN forces, since Zwift itself wouldn’t deal with the villains. ZP makes sure, sort of, that nobody with known better performance in a recent past can join a lower category, and get away with it. Well, you do get away with it. You will still show up as no 1 in the Zwift race report, but ZP will DQ you. So many riders disregard the Zwift results and only look at the ZP results. A bit frustrating to win a race without actually crossing the finish line first, though, don’t you think?

Cruisers

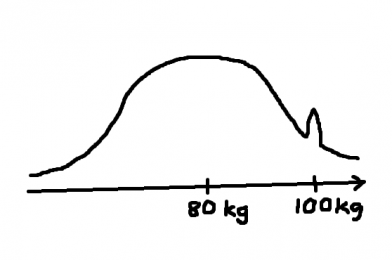

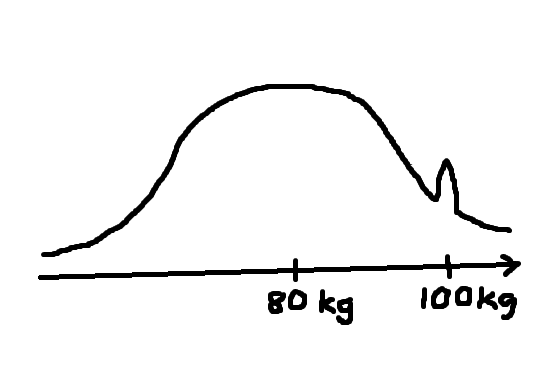

In Zwift you can cheat by exploiting the category system in a way you cannot in e.g. the US cycling federation categories or any other categorization that, similarly, is based on a participants past results. In Zwift categorization is instead based on past perfomance (W/kg), which is not the same as results.

There is no external validation of past performance, meaning as long as you stay within a certain performance band, e.g. an average of 2.6-3.1 W/kg (cat C), in your races, then you ‘belong’ to that category. Zwift will allow you. ZwiftPower will allow you too, as long as you don’t have considerably better performances in your recent (3 months) history. Can you see the opportunities that open up for a cheater here?

You can sign up for races in a category that you are way too strong for and you can win every time and still stay in category, even in the eyes of ZP. In US IRL racing and any other sport or computer game where a results-based category or ranking system is used, this is not possible. Keep winning and you will be auto-moved to the next higher category, against your will if need be. Perform worse than your peers and you will be offered to move down a cat.

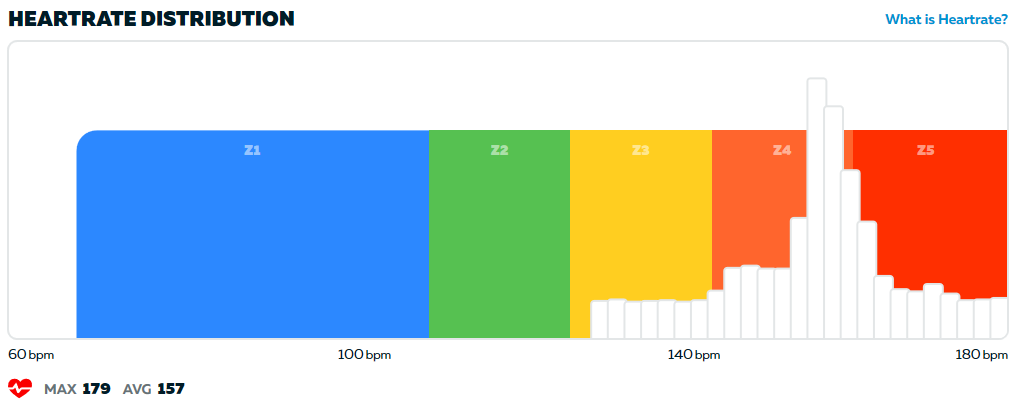

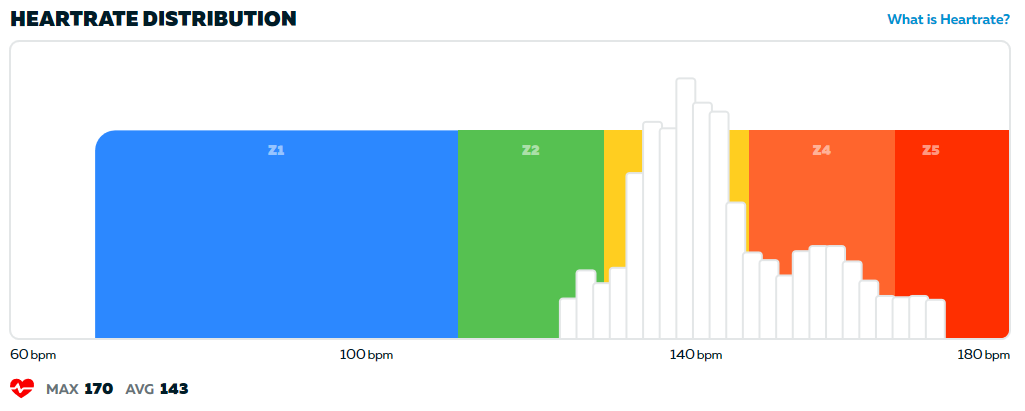

So how do you do it? How do you stay in a category, keep winning more than your fair share, keep fooling ZP? It’s called managed underperformance, or cruising.

What you do is you enter a category below your abilities, keep an eye on your W/kg throughout the race, and try to keep your average W/kg at or below the upper limit of the category. You basically just cruise the race, until you hit a hill or a finish line. That’s when you bring the hammer down and beat the shit out of the low-category low-life peasants!

As long as you don’t hammer your average above the limit you’re fine and in a very good position to win. The only thing you need to worry about are other cheaters like you. You can get carried away racing against them and inadvertently go over limit. The true member of the cat you are racing in, on the other hand, will mostly be at VO2Max at critical moments. They will drop like flies, all while you are merely cruising along.

Know this: I am a cruiser. I will keep cheating by crusing as long as Zwift will allow me. The only thing you can do to stop me is to try bait me above limit. If you succeed you will likely get DQ’d too.

Tagged : Cheating Theory