In the last blog post I tried to show that the majority of races in Zwift and on ZwiftPower seem to be won by riders making a smaller effort than riders coming in behind. As you may have had objections to the methodology, I made new little study which I think you will find more methodologically sound.

Method

I went through all races in cat C starting from the strike of midnight between the 16th and the 17th of Aug 2020, working myself backwards until I had had a look at 100 eligible races. Again, a lot of races had to be discarded due to low attendance or due to a missing link on ZP to the Zwift rider profile page for the race in question.

This time I chose to look at the winner in comparison to the no 4 guy, the guy who didn’t quite make it to the podium. Did any of these riders, winners vs 1st losers, on average, seem to make less of an effort than the others? Effort here is defined as a higher workload in terms of HR distribution over the race. A rider who spends more time in higher HR zones than another rider is considered to have worked harder, made a higer effort.

What is to be expected here? Either we could argue that, all else equal, the winners would make more of an effort on average. If two physically equal riders compete (and they will be equal, on average, with large numbers), then the rider who makes the highest effort would win.

Or we could argue that there should be no difference. Chance, tactics, random occurences, interference by other riders, and powerups may be what decides a race among equals. Everybody should be working roughly equally hard, at least at the top end of the race.

Either of the two scenarios above, or both, is to be considered the baseline, or the null hypothesis, as a scientist would say. If the actual results deviate from this, then it indicates that the null hypothesis isn’t true and that something strange is going on.

What we don’t expect to see here is for the winner to make less effort than the no 4 guy, because that doesn’t make sense. Or, as I would like to argue, it indicates the presence of cruising, i.e. that some riders stay behind in a category, even though they would meet the requirements of a higher category, just to be able to keep winning. By staying within W/kg limits during races they have an advantage over riders who can only reach W/kg limits by giving it their all. The advantage lies in being able to drop people by having reserves and by not riding at VO2Max.

Anyway, I checked the HR distribution graphs of the winner and the no 4 rider in 100 races in cat C and made notes in a table. If the winner made less effort than the no 4, then the race got a ‘1’ in one column, the ‘Oh shit!’ column. If instead the no 4 rider made less effort than the winner OR if there was no clear difference between the respective HR chart, then the race got a ‘1’ in another column, the ‘As expected…’ column.

Results in Cat C

Out of 100 random, consecutive races in cat C, 61 ended up in the ‘Oh shit!’ column, i.e. the winner made less effort than the no 4 guy. Only 39 races showed a no 4 working harder than the winner or no difference between the two of them.

A Comparison

Before we come to any discussion of the results, a comparison with cat A was needed. If there is indeed cruising going on in cat C, then the same should not be true of cat A. Why? Because the hypothesis is that it is the upper performance limit of the categories B-D that creates the incentive to cruise, whereas in cat A there is no upper limit to performance. The harder you go, the better your chances of winning. There is no downside to going too hard as you don’t risk getting a DQ or an upgrade (unless you present superhuman Watts of course).

Scrounging up races in cat A proved to be significantly harder. Not only are there fewer cat A riders, although they are arguably more active on Zwift than the C guys. And in both the cat C study and the cat A study there had to be at least 4 valid participants (according to ZP) in order to do the comparison between the winner and the no 4 guy of course. So a lot of races had to be discarded for this very reason.

Secondly, it is far more common among cat A riders to do a spindown or even to keep riding hard after a race as a prolongation of the race as a training session. And while finish times are not affected if you keep riding after the finish line, your HR distribution graph on Zwift.com is. This made comparisons difficult quite often and led to more discarding of races.

Results in Cat A

During the same time period of the 100 races in cat C, only 52 eligible cat A races were found. Of those only 25 races had a winner making less of an effort than the no 4 guy. 27 races showed no difference or a harder working no 4.

We should keep in mind here that there is actually some room for completely legit cruising in A. I have made no distinction between A and A+. Quite often a race is won by an A+ rider who doesn’t have to go flat out to win. Not only do you not go any harder than you can, you also go no harder than needed – if you are already in the lead, then there is no need to push. Still, over half of the races in cat A showed no such difference.

Conclusions

To me this is yet another piece of evidence showing the presence of cruising in Zwift – whether the cruisers are aware of it or not. And it does seem counter-intuitive that you should be at an advantage making less effort than other contenders. This happens because of the upper performance limit in cat B-D.

You are not allowed to go too hard in cat B-D. It is not forbidden to be too strong though. So as long as you are too strong for your category but manage your performance as to stay within cat limits, then you are a favorite in the race. You don’t always win, but you will win more than your fair share, and you can keep winning indefinitely. ZwiftPower will not upgrade you.

This does not sit well with a sport in my opinion. We should move to a results-based category system, like in real-life sports. Be as strong as you can. Race as hard as you like. Win any race where you are the strongest. But if you keep getting great results in your category time and again over a season, then it’s time for you to get an upgrade. But not because you went too hard but because you did too well too often.

Thus a sandbagger, going well over the current cat limits, will win legitimately but will get an upgrade soon enough into a category where he is no longer that superior and dominant, and you won’t have to face him anymore. And thus a cruiser can still cruise if he likes, i.e. he can still choose to not go too hard in a race, but he can no longer make less effort than you and still win over and over. If he does go for wins, then he will be upgraded, just like the sandbagger, and he will no longer suck your wheel in your races.

A Zwift with results-based categories is a healthier Zwift. And a more fun Zwift. Fun is Fast. And Fun is Fair!

Footnote

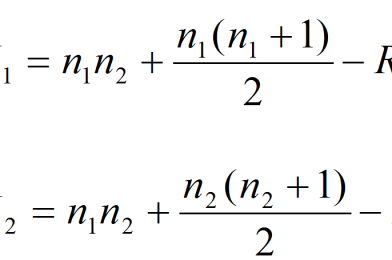

So there was a difference between cat C and cat A but was it just random or what is large enough to be statistically significant, i.e. so large that it is unlikely that it was caused by chance?

We only had 52 races in cat A. Comparing the first 52 races in cat C with the entire sample of cat A with the Mann-Witney U-test, we get a p-value of 0.088. So it’s not statistically significant at a 5% confidence level (although at the 10% level). I will come back with a larger sample, e.g. 100 races in each category, as I am convinced that the difference will stand and will then be statistically significant.