You have probably already heard about weight doping. That by entering a deflated weight in your Zwift profile you will become faster since it will make your W/kg increase. And there is no one around to catch you red-handed if you do this smartly and only participate in everyday races. Only suckers who suddenly drop a nice even chunk, like 10 kg from one day to the next, will look suspicious. ZwiftPower will react to those and so will fellow racers who might be studying their ZwiftPower profiles. Zwift, however, will not react. You can enter any weight you like at any time. And if you race in the lower categories and make sure to decrease your weight in the profile gradually over time, as if you were on a diet, who would dare to call you a cheater? You were just getting fitter and slimmer!

Weight doping, I would assume, could prove to be a big problem in the higher categories. In cat A you only stand to gain if you drop weight, one way or the other, as long as you don’t get caught stating a false weight before a major event where a weigh-in might be required.

Speaking of weigh-ins, has it ever occured to you that real-life racers, as opposed to Zwift racers, don’t weigh in? Think about that for a second or two. “It’s just because we all race alone on top of electronic devices trying to simulate outdoor riding”, you might say. But is it really? Meditate on that for the next 30 min.

Now, here’s the thing. Did you know that the above is not the only form of weight doping in Zwift? Cruisers commonly use another form of weight doping, although I suspect that the general lack of knowledge of the cruiser phenomenon makes it far less conspicuous. We can call what cruisers like to do to stay in cat reverse weight doping. I will explain. But first a lesson in demographics.

What is, realistically, the weight of a Zwifter? Or rather, what is the most common weight in Zwift for, let’s say, a male rider (sorry ladies, but cheating is far more common among male Zwifters). This is where you probably google ‘avg adult male weight’ or something like that. And then you find that in North America, and northern Europe might be similar, it is something like a little over 80 kg or 180 pounds or so. So then the most common weight in Zwift would be 80 kg, right? Let’s pause for a bit and consider.

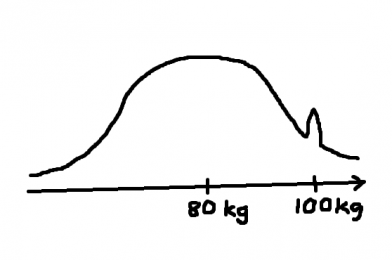

Weight, like most other human characteristics, are normally distributed, a statistician would say. Our weights will fit under a bell-shaped curve, like the badly drawn one I made below.

Imagine you squeeze in all adult males in the Western world under this curve. As you can see, 80 kg is the most ‘roomy’ area under the curve. More guys will fit in there than under other weights, with weights just above or below 80 kg coming pretty close. In the two tails of the curve are the people that either weigh very little or quite a lot. There is far less room for them, meaning there are far fewer of them. So yes, out in the real world something like 80 kg will be the most common adult male weight, with weights around that number coming in close.

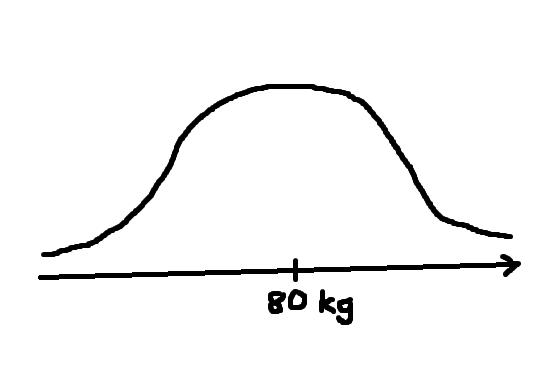

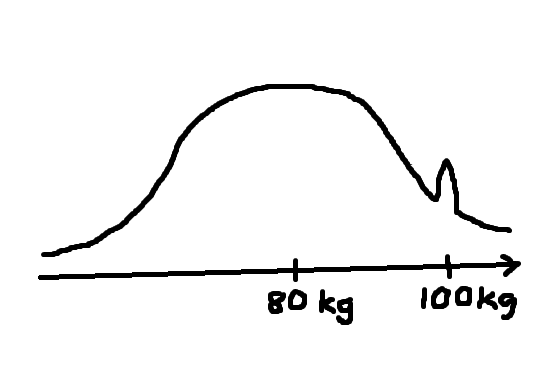

But this is not what the Zwift weight distribution curve would look like, especially not in bottom cat D. First of all, in D it might be somewhat skewed to the right (whereas A and even B might be skewed to the left). Since category is defined by W/kg and since weight affects that ratio, it is only natural that there is an over-representation of the heavy weighters. But if we disregard the skewness, the below curve is what you would find in Zwift cat D (maybe a little exaggerated).

“What’s this spike at 100 kg”, you ask. Well, those are a very special type of cruisers, one that deserves a special mention. Don’t get me wrong, some people do actually weigh in at 100 kg and there is nothing wrong with that. But there are only as many as would fit under a smooth bell curve, skewed or not. The spiky bit would be these special cruisers. What’s so special about them? Why, they are just the cruisers who are bad at maths! (I have seen entire cat D time trial teams consisting of guys each weighing exactly 100 kg for a period!)

It is not uncommon for cruisers to inflate their weight. The reason is that these cruisers are way too strong for their category and need something to hold them down a little so they don’t get green coned or upgraded so easily. It could be any weight really. But why then is 100 kg so common? Because it makes it easier for someone who can’t handle a pocket calculator to keep within cat limits. And it makes running a time trial team much easier. To stay in cat D you must not surpass 2.5 W/kg. If you weigh exactly 100 kg (real or not), the highest Watt number you can average is a nice and even 250W. Now, if weights differ within a team participating in a time trial league, imagine if you at 100 kg would push 250W. Then a team-mate at 87 kg would have to go well over cat limits to stay on your wheel. Your team would fall apart long before the season was over since half the team would get upgraded to cat C! And this is why WTRL is running an esoteric categorization with mixed teams from various categories. It would be impossible to run a TTT league with the standard categories, and you would get massive cheating like in early days of TTT.

There you have it. Reverse weight doping. It’s real. And it’s coming to you courtesy of your friendly neighbor cruiser (not from me though, I don’t cheat with weight). And Zwift made it happen and will allow it. Even ZP will, if you play it right. ZP will try to fight it, but really they are just glueing extra wings to an ostrich. It won’t work, because they are trying to save a category system that was completely whacked from the start. It just won’t work.